During a mid-summer road trip through Ontario we picked up a hitch hiker. Much against my wife Jane’s admonishments, I retrieved a broken, rusted and chipped clock from a roadside park waste bin.

The piece was part of a pile of junk that someone had stuffed into the garbage can where I was also placing our left over picnic lunch.

As I stared into the bin, I could see a dirty clock face and hands. Its cream and gold inlaid appearance distracted me from the other detritus and garbage it lay in. Reaching in, I pulled out a strange assembly: the clock face, some obvious brass works, and a dingy, corroded stand. It stood about 12 inches high, and was clearly abused by water, dirt and rough handling. While I couldn’t recognize the contraption as a time piece, it was easy to conclude that it wasn’t all there– less than whole.

I stuffed the thing into the car trunk, and we left the park.

Finally returning home, I placed the clock on the workshop bench, and prodded at its parts and works, turning it over, inspecting the wheels and gears. They were filthy dirty, and stuck in place. An unloved gadget that was no longer wanted by its owner. But on the face I found the brand name “Solar”. Scrolling through pages of Google listings, I found an image which looked like this clock.

It was on Etsy, and showed a sparkling, clean assembly encased in a glass dome. The piece was called an ‘anniversary clock’. The seller would part with the item for $215 bucks.

Intrigued, I researched ‘anniversary clock’, and learned that these clocks were historic, vintage works of machine art. They originated in America, invented by one Aaron Crane, and patented in 1841. The peculiarity of this antique is that it could run for over a year with only one winding of its mainspring, hence the anniversary.

What was also remarkable about the anniversary clock was its pendulum. Rather than using the familiar swinging ‘bob’ to parcel out the energy of the main spring, it instead periodically twisted a fine wire, back and forth, that suspended four globes beneath the works. They rotate slowly, also back and forth. The wire is almost invisible, thinner than a human hair. This technology is drily called, a torsion pendulum.

I was fascinated by the anniversary concept. I have three other ancient clocks in our home that are all heirlooms, and each requires a bit of love and winding every week. So to wind a clock only once a year… what a feat!

On the clockworks’ back brass plate I found a brand stamped into the metal. ‘FHS’ with tiny clock hands indicating twenty-two after seven, or 7:22 for you digerati. More internet digging, and I confirmed that I had the partial works of a Franz Hermle & Sons clock. It was built in Germany, sometime between 1950 to 1970.

Excited by this discovery, I decided to bring the piece back to life. Knowing next to nothing about clockworks, I approached the big decision: take it apart, or leave it alone?

Go for it!

As I loosened every bolt, I waited for the piece to either explode from a runaway mainspring, or disintegrate into a jumbled paella of gears, nuts and bolts, with no handy instruction manual. I took a lot of pictures to record the disassembly of this foreign object.

During this time I started conversations with clockworks people across the globe, watched Youtube demonstrations, and spent a few dollars obtaining the missing parts. There are thousands of these clocks, sought after, and coveted by collectors. My pursuit included complete disassembly, special cleaning, more research on parts, locating pieces, re-assembly and literally days upon days of testing, which turned into months. I interrupted trips anywhere in the house with a quick visit to the workshop to see if just maybe this time, finally, the clock would still be running.

Occasionally it was, but never for long.

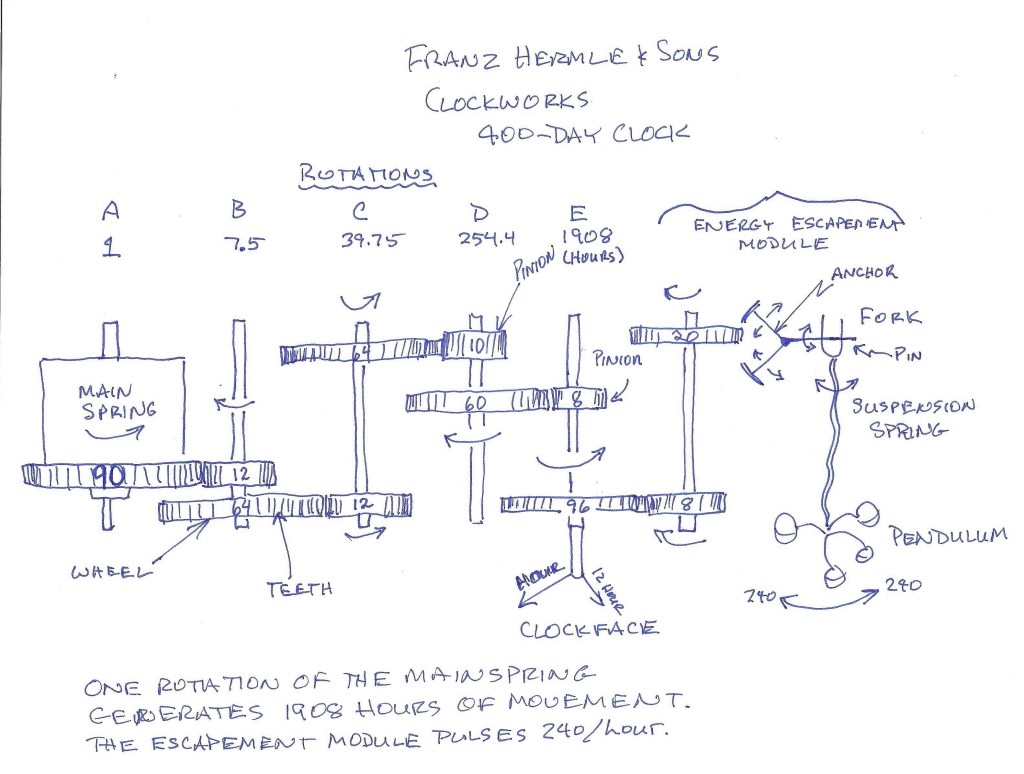

Along the way, I became so familiar with the many wheels, I counted how many teeth each had, which pinions they fit into, and how many turns one wheel would generate on its mated pinion.

The most remarkable find was the power of the 18″ mainspring that was wound tightly inside a brass drum.

The 1-1/2″ diameter drum would complete only one whole revolution in 80 days. One rotation– less than 5 inches. But as the irresistible force drives through four sets of wheels and pinions later, that glacial movement telescopes to over 1,900 rotations of the hour hand. Five rotations of the mainspring: 400 days.

Finally, I have revived the clock. It has a complete assembly of working geared wheels and pinions, bright sparkling components, ultra-sonically washed at a local clock repair shop. Vlad, the technician, shook his head grimly at the possibility that the clock would ever work. He correctly identified a wheel with bent shaft. I ended up buying a new wheel, and put in place, the clock purred its assent.

The Franz Hermle now rests quietly on the work bench. I bought it a brand new shiny glass dome.

I come down to visit it, gaining more confidence that it continues to run without pause. Rescued, serendipitously, from a nasty fate, it silently spins its globes, eight beats to a minute, and subtley pushes its hands past the numerals on its face.

I will wind it up again, next December.