Scanning the shelves of our walk-in closet on a rainy Tuesday afternoon, I stumbled on an old, forgotten box of hockey cards.

I bought these over three decades earlier, and it was a moment of extravagant impulse, paying out a wallet of bills for a small carton of one hundred un-opened wax paper packages. They exuded a sour, sweet smell of aged bubblegum. And teased the prospect of hidden gold.

I don’t make purchases for the sake of locking them away. Not for weeks, let alone years. But there it was, a testament to the impression that ‘trading cards’ made upon me as a child.

In my primary school years, nearing the age of ten, or eleven, every kid had a wad of cards in their pocket: frayed, colorful, bent cardboards held tight by rubber bands. They fit well into back pockets, but best in front to avoid permanent warping.

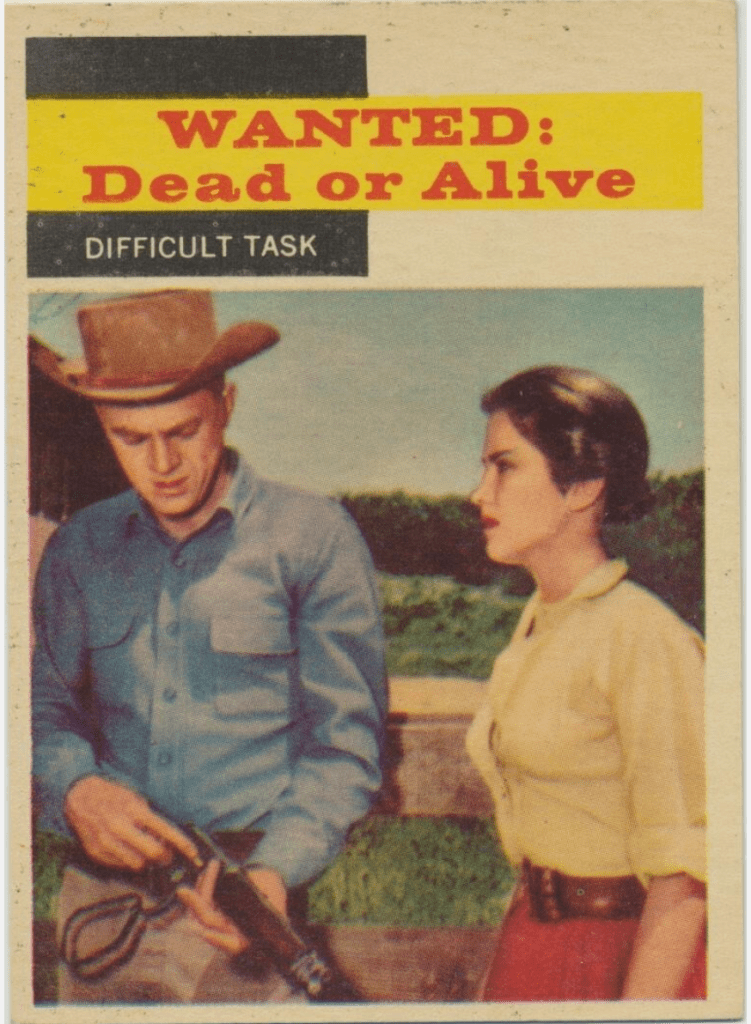

According to the season, we could be collecting hockey cards, football cards, TV show cards, and notably World War 2 collections like “Operation Overlord”. The importance of these collectibles was ownership. As kids, we didn’t own much: bike, hockey stick, puck, baseball glove, pellet gun, jacknife, comics, and a box of special junk which we had filched, found, foraged for, or occasionally bought. The cards, like marbles, were the special treasure in our possession.

Trading cards entered us into an economy. We had collateral, something worth trading, or in most cases, gambling for. Wealth was easily defined by the thickness and heft of your wad of cards. We bought them in nickel and dime packages, and after chewing the accompanying bubble gum, we sorted through the ten or fifteen numbered cards which were randomly included in the purchase.

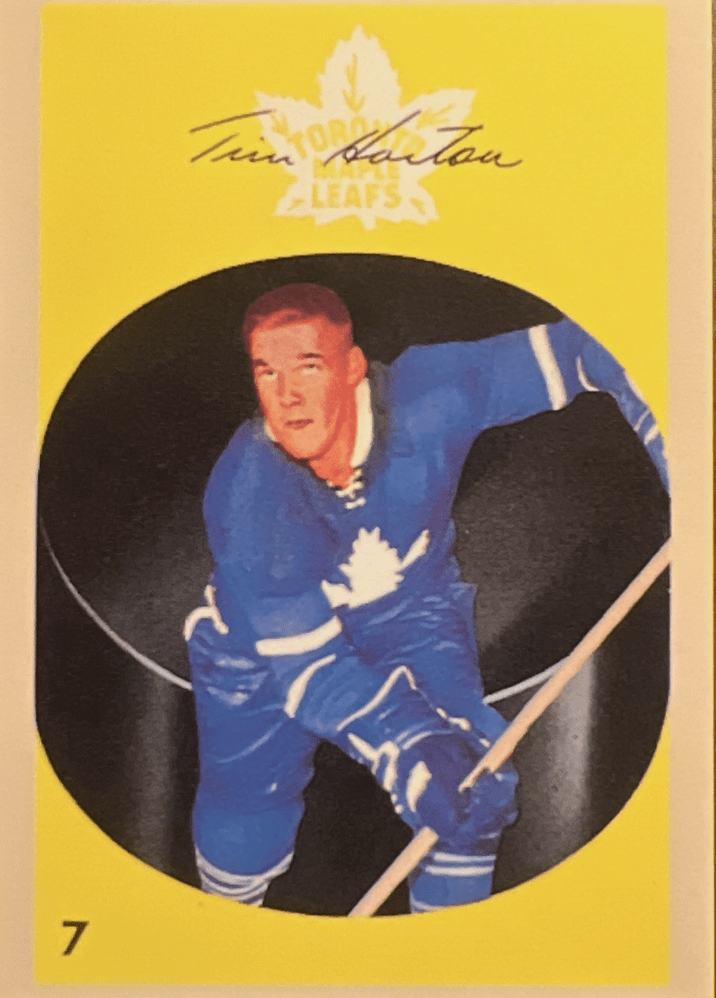

The sortation was essentially to find ‘keepers’. For instance, Maurice ‘Rocket’ Richard was a natural keeper hockey card. Angelo Mosca, the carnivorous Hamilton Tiger Cat football player, too. But if you had more than one, you had a ‘trader’: one to parlay into other missing cards you wanted, held by other kids at school.

The east side of Delhi Public School’s yard had a sizable square of pavement for playing hopscotch, skip-rope, wall-tennis and occasionally hockey. In the fair weather days of early fall and late spring however, the main sport was cards. Numerous pairs of boys were lined up around ten feet from the wall of the red brick school building, making outlandish bets with their cards. The game: closest to the wall wins.

Unlike the Vegas-style, raucous and loudly cheered alley pits to the north side, the cards pitch was quieter, more like a tense game of Texas Hold’em. But the crowds were still present.

Our playing field was the ancient school’s foundation, a three-foot-high wall of dimpled, weathered concrete block, punctuated by large wire-screened basement windows. Essentially, the trick was to spin the 2-1/2″ by 3-1/2″card like a frisbee towards the wall, avoiding the rusted wire screen. Gingerly gripping the piece between two fingers, and flicking the wrist for the right trajectory, the player took aim, and launched the small piece of illustrated sports history. It floated through the air, arcing slightly before descending to slide into place, close to the wall. The competing player, and perhaps more than one, would likewise fire off their respective card.

The closest to the wall won the cards. While the pot was the cards on the pavement, side bets among the players could include additional cards. In this way, fortunes of changed hands– simple objects blown about by errant winds, tripped up on rough asphalt, or flubbed by nervous fingers.

A less challenging and extremely fickle game was ‘odds and evens’. Two opposing players would simultaneously drop a card to their feet, watching it tumble, heads and tails to the ground. During the descent one player would call for an odd, or an even match. This game required no skill and relied entirely upon the immutable laws of physics and binary logic, subject to wind direction.

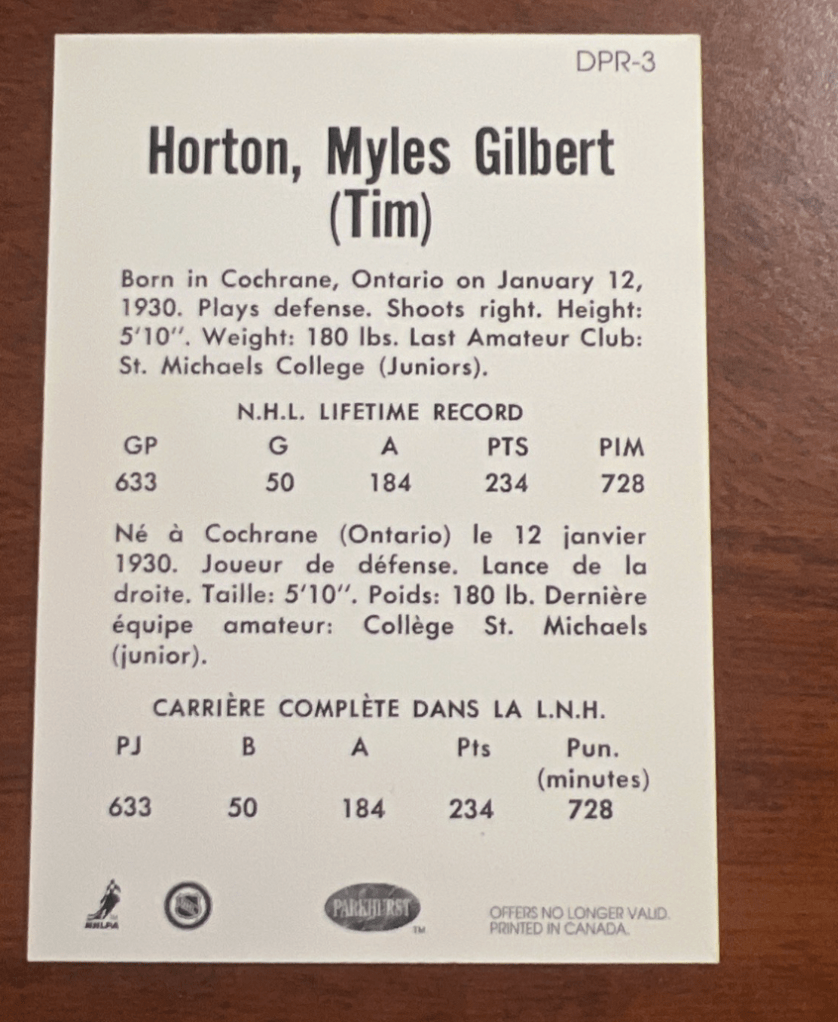

Fortunes were won and lost in these simple contests, and that formed our values and memories for the coming decades. Ironically, the numbered cards held no value except as collections. Few of us really knew the subjects on the colored faces of the cards, let alone the significance of the player statistics quoted on their backs.

Narratives for military cards and TV show cards were context at best, but few told the whole story.

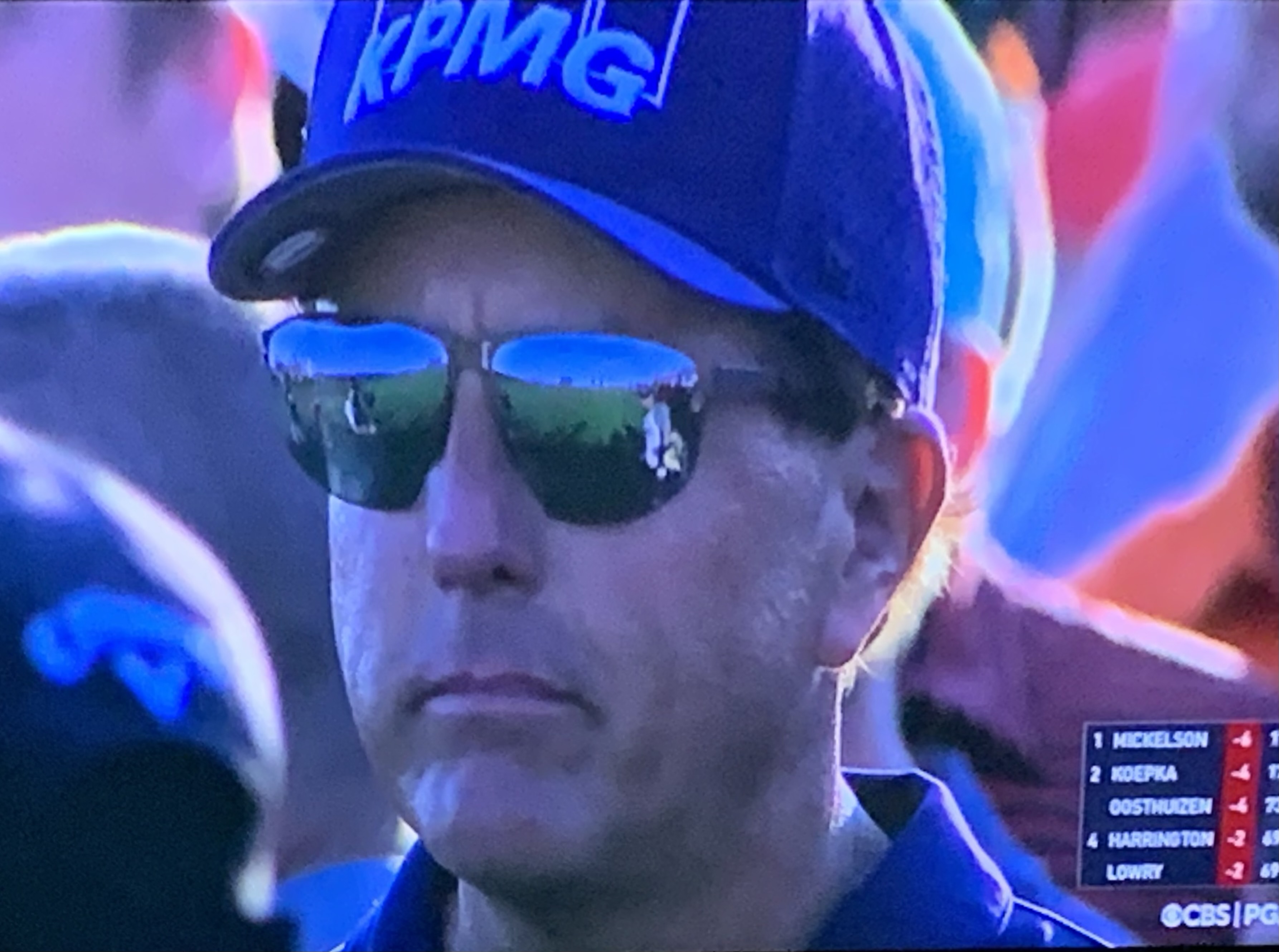

So here I am now, seated in the closet, poring over the sealed collection of card memorabilia. I bought these sets years ago, purely for future value. A 1990 Bowman set of NHL cards– who knows what’s inside? 150 mint-condition images of Hall of Famers? Each one stained with 30-year-old gum? A 2016 set of Topps baseball cards celebrating the beloved Chicago Cubs, returned from 100 years of World Series drought?

Agonized with the thought of thumbing through these pristine, untouched treasures, I return them to their places up on the shelf. Some day, someone else will cross the river, and open the packages. I wish them well.